THE

GOVERNMENT'S DRUGS POLICY: FOLLOW-UP

Submission

of Independent Drug Monitoring Unit

Matthew

J. Atha BSc MSc LL.B & Simon Davis DipHE (SocSci)

to

House

of Commons Home Affairs Select Committee

Foreword

F1

This memorandum represents some of the IDMU research findings

and issues raised in the course of legal casework since

our original submission to the committee enquiry dated

26-9-2001.

F2

IDMU is a small independent research consultancy specialising

in the study of illegal drug consumption patterns, prices

and effects. We are funded wholly via professional fees

earned in providing expert evidence for the criminal and

civil courts, with experience of over 1200 criminal cases

since 1991. The evidence mainly covers personal consumption

and drug valuations, but includes yields of cannabis cultivation

systems, effects of drugs (re criminal intent, driving

impairment etc.), and a range of other aspects, most notably

therapeutic uses of cannabis. Our mission is to provide

accurate, up to date and impartial information on drugs

to all parties to the debate over drugs policy. Other

than legal casework, we have provided consultancy for

GW Pharmaceuticals, the House of Lords enquiry, the Home

Office, Transport Research Laboratory, and Northamptonshire

Police.

1 Lambeth

Experiment

1.1

Fortuitously, IDMU has been monitoring the drug-using

behaviour of survey respondents resident in London who,

since May 2000, have completed questionnaires at the annual

"Legalise Cannabis" festival in Brixton. The

May 2000 data provides baseline figures, June 2001 coincided

with the start of the "experiment" where cannabis

use became effectively tolerated by the police, and May

2002 was a year into the experiment by which time any

consequences of the policy should have started to take

effect.

1.2

The preliminary results of this ongoing study show that

average monthly cannabis usage, purchase and spending

in 2002 had declined slightly, as had the average rating

of cannabis by users. Retail prices paid by Lambeth respondents

showed a slight, but non-significant increase. Cooperative

or commercial purchases were less frequent, with a higher

proportion used by the buyer him/herself. The average

age of initiation to cannabis use increased significantly,

supporting my long-held view that usage would increase

more among the older generation than among teenagers were

the law to be relaxed further, also reflected in the older

average age of the respondents.

|

Lambeth

Experiment - Preliminary Data

|

|

Indicator

|

Year

|

| |

2000

|

2001

|

2002

|

|

Base (no of respondents)

|

338

|

267

|

264

|

|

Response Rate

|

58%

|

70%

|

76%

|

|

Average Age

|

27.23

|

26.81

|

29.01

|

|

Reefers per day (weekdays)

|

5.87

|

5.56

|

4.63

|

|

Reefers per day (weekends)

|

10.66

|

9.6

|

7.31

|

|

Cannabis Used per Month

|

31.73g

|

38.87g

|

27.25g

|

|

Cannabis purchase per month

|

41.18g

|

57.68g

|

31.58g

|

|

Avg % personal use

|

77%

|

67%

|

86%

|

|

Monthly Cannabis Spending

|

£ 67.58

|

£ 73.11

|

£ 74.99

|

|

Cannabis Rating (0-10)

|

8.51

|

8.48

|

8.29

|

|

Soap-Bar Resin 1/8oz price

|

£ 12.86

|

£ 12.36

|

£ 12.91

|

|

Resin oz price

|

£ 69.93

|

£ 61.22

|

£ 65.68

|

|

Resin 9oz

|

£ 446.11

|

£ 393.64

|

£ 298.75

|

|

Skunk Herbal 1/8oz

|

£ 21.07

|

£ 20.52

|

£ 20.69

|

|

Skunk oz

|

£ 121.61

|

£ 119.85

|

£ 125.48

|

|

Skunk 9oz

|

£ 740.00

|

£ 640.91

|

£ 883.33

|

|

Age 1st Use of Cannabis

|

15.61

|

15.26

|

16.12

|

1.3

The preliminary conclusions to be drawn are that the Lambeth

experiment appears to have made little difference to the

consumption of cannabis users, but that any effect would

appear at this stage to be moderating influence on cannabis

usage rather than encouragement. Fears of increased cannabis

usage as a result of the experiment would thus appear

unfounded.

2. Drug

Prices

2.1

Cannabis: Prices of cannabis resin are continuing

to fall around the country as a whole, although there

are signs of the price of cannabis resin "bottoming

out", with the typical price now £10 per 1/8oz rather

than £15 in the mid 1990s, and a 9oz bar being sold for

£250-£400 rather than £600-£800 in 1994. Skunk (domestically

produced) cannabis prices appear relatively stable, with

the typical price ranging from £15-£25 per 1/8oz, and

ounces from £100-£160. Imported cannabis bush remains

rare, although has been encountered more often in IDMU

Criminal cases over the past 12 months, with these prices

increasing slightly. More respondents are reporting "exotic"

cannabis resin varieties such as moroccan "pollen".

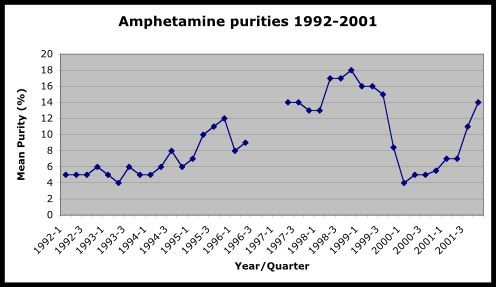

2.2

Stimulants: Purities of amphetamine appear to have

returned to the levels seen in the late 1990s, gram prices

remain relatively stable within a range of £5 to £10,

although "ounce" prices appear to have increased

from £50-£80 to £70-£100 over the past two years. There

is still no evidence of any significant levels of methamphetamine

use (crystal meth, crank, ice etc) in the UK, despite

an epidemic in the USA. There are isolated seizures, mainly

in tablet form or powder sold as amphetamine sulphate.

Sensationalist publicity for methylamphetamine should

be avoided at all costs, lest it create a demand which

does not currently exist. The precursors used to manufacture

methamphet include over the counter medications and household

cleaning materials, thus no control on the availability

or tracking of precursor chemicals would be practicable

were usage of this drug to become commonplace.

2.3

Cocaine prices have remained stable within a range of

£40-£60 per gram, and £500-£1200 per ounce. Purities are

stable or rising. Crack prices again remain relatively

stable, but highlyvariable, with rocks of different sizes

available in different price bands.

2.4

Ecstasy prices are continuing a dramatic fall from £10-£15

per tab in 1994, down to £3-£5 per tab in 2002, with similar

falls at wholesale levels where prices of £1 or less per

tab are now common. Fewer "bogus" tablets are

being encountered, due to increased availability and use

of DIY pill-testing kits, most tablets sold as Ecstasy

contain 50-100mg MDMA.

2.5

Heroin prices are in long term decline. A "tenner

bag" may still cost £10, but whereas in 1994 it might

contain 80-100mg, these days they contain 100-250mg, and

£5 bags of around 100mg are increasingly common. Gram

prices vary across the country in a range of £30-£80,

ounces £500-£1000.

2.6

The Court of Appeal held in R-v-Edwards [2001]

that evidence in court by police officers or defence experts

as to drug consumption and prices would be ruled inadmissible

hearsay unless supported by statistical or scientific

evidence. In many cases prosecutions are undermined by

excessive valuations of drugs by police officers, many

of whom display a woeful ignorance of the drugs market

(e.g. claiming cannabis or cannabis resin is sold by the

gram), and who quote prices which those drug users among

the jury (statistically around 3-4 jury members will have

used cannabis or other drugs at least once, and 1-2 members

may be regular users familiar with current prices).

3 Drug

Prevalence (among drug users as a whole)

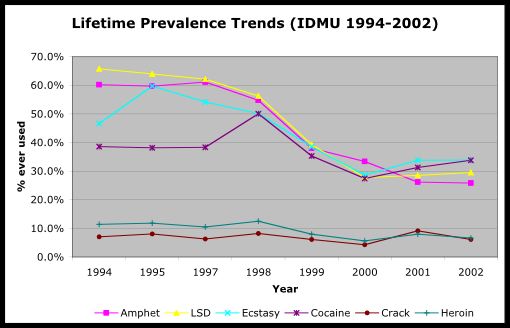

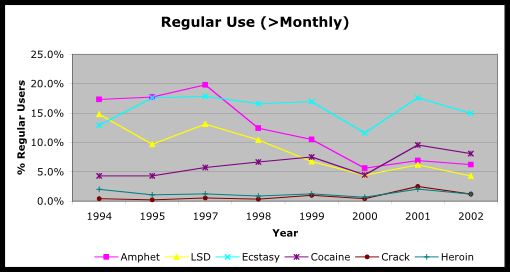

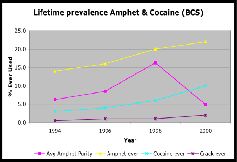

3.1

The prevalence of use of other controlled drugs among

users as a whole has declined since our 1994 survey, however

regular use of cocaine and crack has increased (the apparent

decrease in 2000 due to a survey design flaw which left

such questions to the end of a long and complicated survey,

causing a much higher proportion of incomplete questionnaires).

The decline in usage of other controlled drugs may reflect

increasing social acceptability of cannabis and use by

a wider segment of the population, not restricted to pre-existing

"drug subcultures" where use of different drugs

is tolerated.

3.2

It would appear that the popularity of ecstasy has passed

its peak, with fewer users reporting regular use, despite

the dramatic fall in price. Whether this reflects a decline

in the dance culture, maturation out by the first waves

of ecstasy users, or increasing concerns about the long-term

mental health risks of ecstasy use remains an open question.

3.3

It is clear that with drugs other than cannabis, experimental

and occasional use remains the norm, with a very small

proportion using daily. The proportion of daily users

to lifetime, or regular, users is highest for heroin and

crack cocaine. However even with these "hard"

drugs, the majority who try them, or use occasionally,

do not become dependent.

4. Supply-side

Interventions - Operation Pirate

4.1

Operation Pirate led to the discovery in late 1998 of

the largest illicit drugs laboratory operation ever uncovered

on mainland Britain which saw 10 men sentenced for a total

of over 40 years for being part of a multi-million pound

amphetamine production conspiracy1

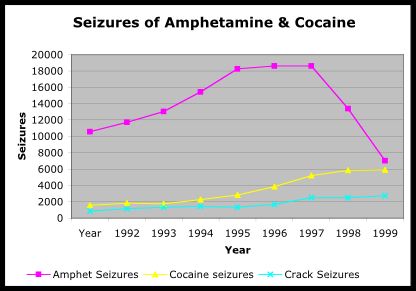

4.2

While usage of amphetamine by young people had been increasing

throughout the 1990s, with 8% of 16-29 year olds using

the drug in 1998, by 2000 that figure had fallen to 5%,

and the average purity had fallen from 16% to 5%, before

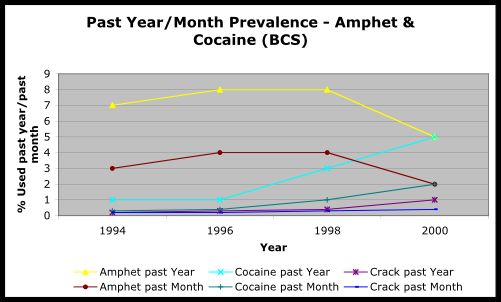

returning to pre-operation levels towards the end of 2001.

1

http://www.nationalcrimesquad.police.uk/Hot_off_the_press/info/106_record_jail_terms.html

4.3

Prosecutions and seizures for amphetamine also fell sharply,

with the total number of amphetamine seizures falling

from over 18600 in 1998 to just over 7000 in 2000. A major

victory in the War on Drugs · or was it?

4.4

Britain"s "speed" users were suddenly left

without amphetamine to satisfy their cravings, at the

same time as record amounts of cocaine and crack were

entering the UK. Consequently although use in the past

year and past month of amphetamine halved between the

1998 and 2000 British Crime Surveys, usage of cocaine

and crack had doubled, such that by 2000 an equal number

had used amphetamine and cocaine in the previous 12 months.

4.5

The implications of this finding for supply-side control

and interdiction policies are gloomy. The most successful

anti-drugs operation in recent UK history merely resulted

in a high proportion of amphetamine users switching to

cocaine, and possibly also crack. One reason the UK never

experienced the US "crack" epidemic of the late

1980s and early 1990s, and for the relatively low prevalence

of cocaine usage, has been the wide availability of amphetamine,

which provides a similar effect for a longer duration

at a fraction of the cost.

4.6

The argument for "legalising" amphetamine is

undone by the propensity of the drug to cause aggression

and violence if used to excess, as well as physical health

risks associated with all stimulants. Thus an unrestricted

retail market would have adverse consequences for public

order and safety. Nonetheless, a form of controlled availability

- e.g. re a smart card for registered users specifying

a maximum daily or weekly "ration"/dose, or

prescription by GPs of dexamphetamine tablets or linctus

(to prevent injection) - might represent an alternative

method of "maintenance" treatment for individuals

with cocaine or crack dependency problems.

5. Medicinal

Necessity (Cannabis)

5.1

I am possibly the busiest court expert in this field,

having been involved as an expert in over 150 court cases.

Where a defence of medical necessity (duress of circumstances)

is put before a jury and supported by credible medical

evidence of a relevant condition, the jury almost always

acquits.

5.2

The principle of medical necessity in such cases has been

approved by the Court of Appeal in the case of Lockwood

[2002] · ironically one of the few defendants to have

been convicted. The defence has successfully been used

by patients with multiple sclerosis, chronic pain, epilepsy,

irritable bowel disease, cancer chemotherapy, gout, arthritis,

asthma, stress, anxiety, depression and Opiate dependency,

among other conditions, with juries tending to give a

wide interpretation to what is meant by "serious

injury". Where the defence is a mere "smokescreen"

to avoid conviction of dealing cannabis to non-patients,

juries rightly continue to convict.

5.2

Nonetheless, the Crown Prosecution Service almost invariably

proceed to trial in such cases, rather than abandoning

the prosecution when a medicinal defence is presented.

Despite my advice to both the Lords and Commons enquiries,

there are as yet no national guidelines as to which conditions

could provide a reasonable defence to cannabis possession

and/or cultivation charges. Each case must be examined

on its individual merits, but all such decisions to prosecute,

or continue with a prosecution, should first be reviewed

by a medical expert or panel of experts with the power

to discontinue proceedings where there is clear merit

in the defence, before further public money is wasted

on a jury trial.

6.

Implications of Reclassification

6.1

In our original submission of September 2001 we drew attention

to the pros and cons of different approaches to drug policy.

Our view remains that reclassification represents mere

tinkering at the edges of policy reform, where a root

and branch change could bear real results.

6.2

Our concern is that reclassification may make little difference

to the problems (social and financial) which drugs cause

society, unless the changed status is reflected in police

attitudes. It is the criminal record acquired by the user

which causes most damage to his or her future prospects,

irrespective of the penalty which results from it.

6.3

I can envisage a situation where some police officers

or forces allege "intent to supply" on ever-smaller

quantities of drugs, to "improve" their compliance

with performance targets, or to give themselves additional

powers (e.g. s18 PACE search) following an arrest. This

trend appears increasingly evident already, particularly

in rural forces (where users may have to travel to buy

their drugs and consequently buy more for themselves when

they have the opportunity). I would estimate that somewhere

around 60% or more of persons convicted of drugs supply

offences plead guilty on the basis of social supply (to

partner or friends) yet are convicted, on their record,

as drug dealers, but pleading (despite protestations of

innocence) due to the fear of being found guilty and imprisoned

as a result.

6.4

There should be national guidelines issued to police forces

for the quantities of drugs which would:

(a)

involve no action (e.g. up to 30g cannabis or up to 15

flowering plants)

(b)

charged with possession only (30-100g cannabis, 15-50

plants)

(c)

charged with possession only, unless there is supporting

evidence of dealing (cash, packaging materials, scales,

wrapped deals, dealer lists or documentations) where "intent"

charges might be brought (100-250g cannabis, 50-100 plants)

(d)

where intent charges may reasonably proceed on the basis

of quantity alone (over 250g cannabis or 100+ plants)

(e)

The burden of proof would remain on the prosecution to

prove an "intent" charge, based (e.g.) on the

defendant"s ability to fund a claimed level of usage

without resorting to dealing drugs.

6.5

For other drugs, the equivalent thresholds could reasonably

be

|

Drug

|

No

action

|

Poss

only

|

Poss

unless intent

|

Intent

|

|

Amphet

|

0-7g

|

7-20g

|

20-50g

|

>50g

|

|

Ecstasy

|

1-10 tbs

|

10-50tbs

|

50-100tbs

|

>100 tbs

|

|

LSD

|

1-10 tbs

|

10-50tbs

|

50-100tbs

|

>100 tbs

|

|

Cocaine

|

0-2g

|

2-10g

|

7-30g

|

>30g

|

|

Heroin

|

0-1g

|

1-4g

|

5-14g

|

>14g

|

|

Crack

|

0-1g

|

1-2g

|

2-10g

|

>10g

|

6.6

In the longer term, a coherent control policy would involve

controlled availability of different drugs according to

their potential dangers to the individual user and to

society.

6.7

Cannabis could be treated in a similar manner to tobacco

or alcohol, although to reduce the present availability

to children I would consider members-only clubs to be

the most appropriate legal outlet.

6.8

Stimulant drugs should be rationed, to deter the user

from consuming excessively and creating social problems

as a result, with cocaine users encouraged to use amphetamine

as a marginally safer alternative.

6.9

Heroin should be made available to existing users (verified

by urinalysis) on prescription, in an injectable or smokeable

form (e.g. laced cigarettes), as a matter of urgency,

in order to undercut the illicit market and make a significant

impact on acquisitive crime, as well as helping to stabilise

the chaotic lifestyles associated with problem use.

|

Controlled

Availability?

|

|

Cannabis

|

Licensed

premises (coffee shops or members-only clubs), excise

duty

|

|

Tobacco

|

Licensed

premises, excise duty

|

|

Alcohol

|

Licensed

premises, excise duty

|

|

Amphetamine

|

Prescription

only or rationing (smart card)

|

|

Cocaine

|

Prescription

or rationing (smart card), low dose preparations

(e.g. coca leaf), alternative stimulants (maintenance)

|

|

Heroin

|

Prescription

or rationing (smart card), low dose preparations

(e.g. opium)

|

|

Ecstasy

|

Rationing

(smart-card) · develop safer but effective legal

alternatives

|

|

Crack

|

No

availability, users could prepare from cocaine "ration"

alternative stimulants

|

6.10

The financial argument for licensing of cannabis (or other

drugs) has never convincingly been aired. There is no

doubt that substantial funds would become available to

the Treasury as a result of excise duty, although the

dramatic fall in prices of cannabis and ecstasy in recent

shows the limitations of any fixed duty levels.

6.11

Already the UK is moving towards self-sufficiency in cannabis,

with nearly 50% of the market now involving domestically-produced

(indoor) material. However any moves to licence the sale

of any currently illegal drug would require secession

from, or renegotiation of, existing international treaties.

I note the move towards reclassification has been criticised

by members of the the UNDCP executive. However as these

represent the very people who have presided over the failures

of international drugs policy for the past 30+ years,

such criticism is an understandable response to proposals

which could overturn their world view, particularly where

alternative approaches (e.g. the Netherlands) have proven

successful in reducing both the level of drug use and

of drug-related harm.

Matthew

Atha - Director

Simon

Davis -Research Co-ordinator

6

March 2003