|

|

Some articles have not been moved to our new site yet.

As a result you have been redirected to our old site.

If you wish to return to our new site - click here.

Cannabinoids

and Multiple Sclerosis

Introduction

& Overview

Multiple

sclerosis is a disease of the brain and spinal cord

caused by demyelination (loss of the insulating sheath)

of nerve fibres, believed to be caused by some substance

dissolving or breaking-up fatty tissue of the nerve-sheath[1]. The condition is progressive but varies

in intensity, with remission of symptoms and relapse

commonly reported. Common symptoms include fatigue,

balance problems, muscle weakness, incontinence, muscle

spasms, pain and tremor.[2]

Current

treatments for MS are of little benefit, expensive,

and with risks of side effects. Alpha & º-interferon,

and corticosteroids have been found to have some value,

but symptoms are poorly-controlled by existing medications,

and no cure has been found. Many patients are unable

to tolerate the side-effects of conventional medication[3]

This

section reviews and describes the published scientific

evidence relating to the use of cannabis and cannabinoids

in the treatment of multiple sclerosis symptoms, and

the involvement of endocannabinoids in the development

of the MS disease process. Scientific developments in

this field are rapidly advancing, with an average of

one paper published every ten days over the past four

years since my last review of this field. Over that

period the results of many clinical trials have been

published, and the state of basic research into the

disease process has advanced dramatically.

Anecdotal

Evidence & Surveys

The

potential effect of cannabis on the symptoms of multiple

sclerosis were first reported by sufferers of the disease

introduced to cannabis by recreational or social users.

Such anecdotal evidence (i.e. not backed up at the time

by clinical assessment, animal or theoretical basis,

nor by clinical trials) includes case studies and self-completion

surveys.

Grinspoon[4] reports a number of anecdotal reports

of dramatic improvement in MS symptoms attributed to

marijuana (cannabis) use. Initially, these were unexpected

findings following social use of the drug. In one account,

Greg Paufler described a progressive degeneration, following

onset of MS in 1973, to bedridden status, and severe

side effects (dramatic weight gain, addiction to benzodiazepines)

from prescribed medicines. Following several social

åjoints" one evening, he astonished family and

friends by standing spontaneously for the first time

in months. He subsequently found that his symptoms deteriorated

without the drug, but improved dramatically during periods

when he was smoking cannabis. Grinspoon reviewed further

cases showing improvements in muscle spasms, tremor,

continence, ataxia (loss of muscle control) and insomnia.

Clare Hodges, an MS patient giving oral evidence to

the House of Lords enquiry, reported cannabis ågreatly

relieved" physical symptoms including discomfort

of bladder and spine, nausea and tremors, and stated

åCannabis helps my

body relax, I function and move much easier. The physical

effects are very clear, it is not just a vague feeling

of well-being."

In

a study of 112 MS patients self-medicating with cannabis

in the US and UK, Consroe et al[5] reported that 70% of more respondents

reported improvement in the following symptoms:

| |

Spasticity

at sleep onset

|

Pain

in muscles

|

| |

Spasticity

when awaking at night

|

Pain

in legs at night

|

| |

Tremor

(arms/head)

|

Depression

|

| |

Anxiety

|

Spasticity

when waking in morning

|

| |

Spasticity

when walking

|

Tingling

in face/arms/head/trunk

|

| |

Numbness

of chest/stomach

|

Pain

in face

|

| |

Weight

loss

|

Weakness

in legs

|

The authors considered these reports åstrongly

suggested cannabinoids may significantly relieve symptoms

of MS, particularly spasticity and pain",

and provided sufficient grounds for a properly controlled

clinical trial to test such claims objectively and conclusively.

A

German study[6] of 170 self-medicating cannabis users

found 11% of respondents reported using the drug successfully

in managing MS symptoms, the second most common use

behind depression, and concluded "this study demonstrates a successful use of cannabis

products for the treatment of a multitude of various

illnesses and symptoms. This use was usually accompanied

only by slight and in general acceptable side effects."

Mechoulam[7] reviews illegal use of

cannabis by MS patients. In a UK survey of 318 MS patients[8], 8% reported

using cannabis to relieve symptoms.

In

a survey of 780 MS patients in Canada, Page et al[9] found

"Forty-three percent had tried cannabis at some point

in their lives, 16% for medicinal purposes. Symptoms

reported to be ameliorated included anxiety/depression,

spasticity and chronic pain" and concluded

"Subjective improvements

in symptom experience were reported by the majority

of people with MS who currently use cannabis."

A survey of 131 patients with amytrophic lateral sclerosis[10], of which only 13 used cannabis, found

"cannabis may

be moderately effective at reducing symptoms of appetite

loss, depression, pain, spasticity, and drooling".

Simmons et al[11] studied responses to an internet survey

by 2529 respondents, finding cannabis commonly reported

as beneficial. Clarke et al[12] surveyed 220 MS patients in Canada,

finding "Medical

cannabis use was associated with male gender, tobacco

use, and recreational cannabis use. The symptoms reported

by medical cannabis users to be most effectively relieved

were stress, sleep, mood, stiffness/spasm, and pain."

Ware et al[13] reported

results of a survey of medicinal cannabis use in the

UK, noting "Medicinal cannabis use was reported by patients with

chronic pain (25%), multiple sclerosis and depression

(22% each), arthritis (21%) and neuropathy (19%). Medicinal

cannabis use was associated with younger age, male gender

and previous recreational use (p < 0.001)."

In

the Netherlands, cannabis has been available on prescription

from pharmacies since September 2003, Erkens et al[14] followed up 200 patients

prescribed the drug with a questionnaire survey, finding

"Cannabis was mainly used for chronic pain and muscle

cramp/stiffness.The indication of medicinal cannabis

use was in accordance with the labeled indications.

However, more than 80% of the patients still obtained

cannabis for medicinal purpose from the illegal circuit.

Because of the higher prices in pharmacies, ongoing

debate on the unproven effectiveness of the drug and

the hesitation by physicians to prescribe cannabis."

Animal

studies

Scientists

have developed animal models for MS in rats, mice and

guinea-pigs in the form of an experimental autoimmune

encephalomyelitis (EAE). In guinea-pigs, Lyman et al[15] found 98% of animals treated with placebo

died, whereas 95% of THC-treated animals survived the

disease process, with much reduced inflammation of brain

tissue. In rats, Wirguin et al[16]

found ∆8THC

significantly reduced neurological deficits in two strains

of EAE inoculated rats.

Baker

et al[17], studying tremor and spasticity in mice,

concluded: "The

exacerbation of these signs after antagonism of the

CB1 and CB2 receptors, notably the CB1 receptor... indicate

that the endogenous cannabinoid system may be tonically

active in the control of tremor and spasticity. This

provides a rationale for patients' indications of the

therapeutic potential of cannabis in the control of

the symptoms of multiple sclerosis, and provides a means

of evaluating more selective cannabinoids in the future."

Achiron et al[18]

studying rats, found reduction in the inflammatory response

in the brain and spinal cord in animals treated with

dexanabinol, a synthetic cannabinoid, and concluded

"dexanabinol

may provide an alternative mode of treatment for acute

exacerbations of multiple sclerosis (MS)".

Pop[19] reviews the development of dexanabinol,

a non-psychoactive cannabinoid and NMDA antagonist developed

by "Pharmos Corp for the potential treatment of cerebral

ischemia... and multiple sclerosis (MS)"

commenting "A Notice of Allowance was received in March 1999 on

a patent covering the use of the drug in the treatment

of MS [324163]. The use of dexanabinol and its derivatives

to treat MS is described in US-05932610 [358503]."

Fernandez-Ruiz[20] noted "Data,

initially anecdotal, but recently supported on more

solid experimental evidence, suggest that cannabinoids

might be beneficial in the treatment of some of the

symptoms of multiple sclerosis (MS). Despite this evidence,

there are no data on the possible changes in cannabinoid

CB(1) or CB(2) receptors, the main molecular targets

for the action of cannabinoids, either in the postmortem

brain of patients with MS or in animal models of this

disease (EAE)", concluding "generation

of EAE in Lewis rats would be associated with changes

in CB(1) receptors in striatal and cortical neurons,

which might be related to the alleviation of some motor

signs observed after the treatment with cannabinoid

receptor agonists in similar models of MS"

Baker et al[21] found "In

areas associated with nerve damage, increased levels

of the endocannabinoids... were detected"

and concluded "These

studies provide definitive evidence for the tonic control

of spasticity by the endocannabinoid system and open

new horizons to therapy of multiple sclerosis, and other

neuromuscular diseases, based on agents modulating endocannabinoid

levels and action, which exhibit little psychotropic

activity."

Recent

studies of the biological basis of MS largely confirm

the efficacy of cannabinoids in relief of muscle spasticity,

including the endogenous cannabinoids amandamine and

2-arachidonoyl glycerol[22], and

by dexanabinol via non-receptor mediated reduction of

inflammation[23].

Baker at al[24] considered research to have demonstrated

"definitive evidence

for the tonic control of spasticity by the endocannabinoid

system". In a series of reviews of the

implications of recent fundamental cannabinoid research

on therapeutic potential, Pertwee[25][26] stated:

"...uses for

CB1 receptor agonists include the suppression of muscle

spasm/spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis...".

The main active constituent of cannabis - THC is one

such CB1 receptor agonist.

Killistein

et al[27] concluded "endogenous

cannabinoids appear to play an important role in signal

transduction, which may be starting points for therapy

regarding... multiple sclerosis" Klein

et al[28] reported "The

effect of cannabimimetic agents on the function of immune

cells such as T and B lymphocytes, natural killer cells

and macrophages has been extensively studied over the

past several decades using human and animal paradigms

involving whole animal models as well as tissue culture

systems. From this work, it can be concluded that these

drugs have subtle yet complex effects on immune cell

function and that some of the drug activity is mediated

by cannabinoid receptors expressed on the various immune

cell subtypes... Further studies will define the precise

structure and function of the putative immunocannabinoid

system, the potential therapeutic usefulness of these

drugs in chronic diseases such as acquired immune deficiency

syndrome and multiple sclerosis" Lambert

et al[29], studying N-palmitoylethanolamine (PEA),

an analogue of anandamide, found "PEA

is accumulated during inflammation and has been demonstrated

to have a number of anti-inflammatory effects... It

is now engaged in phase II clinical development, and

two studies regarding the treatment of chronic lumbosciatalgia

and multiple sclerosis are in progress."

Brooks et al reported "Activation of cannabinoid receptors causes inhibition

of spasticity, in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis",

finding that Arvanil, a "structural

"hybrid" between capsaicin and anandamide,

was a potent inhibitor of spasticity at doses (e.g.

0.01 mg/kg i.v.) where capsaicin and cannabinoid CB(1)

receptor agonists were ineffective"

Wilkinson

et al[30], studying a mouse model of MS, found

"Whilst (cannabis

extract) inhibited spasticity in the mouse model of

MS to a comparable level, it caused a more rapid onset

of muscle relaxation, and a reduction in the time to

maximum effect compared with Delta9THC alone. The Delta9THC-free

extract or cannabidiol (CBD) caused no inhibition of

spasticity" concluding re antispasticity

"Delta9THC was the active constituent, which might

be modified by the presence of other components"

Ni et al[31]

noted "Cannabinoid

receptor agonists have been shown to downregulate immune

responses and there is preliminary evidence that they

may slow the progress of MS." Raman

et al[32] found

"Administration

at the onset of tremors delayed motor impairment and

prolonged survival in Delta(9)-THC treated mice when

compared to vehicle controls" Mestre

et al[33] concluded

their results to suggest "manipulation

of the endocannabinoid system as a possible strategy

to develop future MS therapeutic drugs"

Weydt et al[34] noted the effect on ALS-induced

mice of non-psychoactive CBN (cannabinoid) "significantly

delays disease onset by more than two weeks while survival

was not affected"

Ortega-Gutierrez

et al[35] found that in mice, an anandamide reuptake

inhibitor UCM707 would "reduce

microglial activation, diminish major histocompatibility

complex class II antigen expression, and decrease cellular

infiltrates in the spinal cord. Additionally, in microglial

cells, UCM707 decreases the production of the proinflammatory

cytokines tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, interleukin

(IL)-1beta, and IL-6; reduces nitric oxide levels and

inducible nitric oxide synthase expression; and is able

to potentiate the action of a subeffective dose of the

endocannabinoid anandamide. Overall, these results suggest

that agents able to activate the endocannabinoid system

could constitute a new series of drugs for the treatment

of MS." De Lago et al[36]

found "UCM707,

like other endocannabinoid uptake inhibitors reported

previously, significantly reduced spasticity of the

hindlimbs in a chronic relapsing EAE mice, a chronic

model of MS."

Studying

mice, Arevalo-Martin et al[37] found "cannabinoids reduced microglial activation, abrogated

major histocompatibility complex class II antigen expression,

and decreased the number of CD4+ infiltrating T cells

in the spinal cord. Both recovery of motor function

and diminution of inflammation paralleled extensive

remyelination" and concluded there were

"potential therapeutic

implications in demyelinating pathologies such as MS;

in particular, the possible involvement of cannabinoid

receptor CB2 would enable nonpsychoactive therapy suitable

for long-term use." Croxford & Miller[38] found "cannabinoids

are useful for symptomatic treatment of spasticity and

tremor in chronic-relapsing experimental autoimmune

encephalomyelitis. Cannabinoids, however, have reported

immunosuppressive properties. We show that the cannabinoid

receptor agonist, R+WIN55,212, ameliorates progression

of clinical disease symptoms in mice with preexisting

TMEV-IDD"

In

rat model of MS (CREAE), Cabranes et al[39] reported

"CB(1) receptors

were affected by the development of CREAE in mice exhibiting

always down-regulatory responses that were circumscribed

to motor-related regions and that were generally more

marked during the acute and chronic phases. These observations

may explain the efficacy of cannabinoid agonists to

improve motor symptoms (spasticity, tremor, ataxia)

typical of MS in both humans and animal models."

Human

studies

Several

researchers[40][41][42] have

commented upon the difficulties involved in conducting

proper research on the effects of cannabinoids on medical

conditions, including MS, in the light of the legal

status of cannabis. Robson[43] comments "the methodological challenges to human research involving

a pariah drug are formidable"

Petro

& Ellenberger[44], in a small double-blind clinical trial

found 10mg THC significantly (p<.01) reduced spasticity

in patients with MS or similar conditions, compared

to placebo. In an earlier double-blind crossover trial,

Ungerleider et al[45] reported åAt

doses greater than 7.5 mg there was significant improvement

in patient ratings of spasticity compared to placebo.

These positive findings in a treatment failure population

suggest a role for THC in the treatment of spasticity

in multiple sclerosis." Clifford[46], in a trial involving

8 patients severely disabled with tremor and ataxia,

reported significant improvement in two patients. Case

study reports[47][48]

suggest that cannabis can suppress pendular nystagmus

(jerky eye movements) in patients with multiple sclerosis.

In

a pilot study involving two patients, Brenneison et

al[49]

reported "Oral

and rectal THC reduced at a progressive stage of illness

the spasticity, rigidity, and pain, resulting in improved

active and passive mobility." In a single

case double-blind trial, Maurer et al[50] found THC "showed

a significant beneficial effect on spasticity. In the

dosage of THC used no altered consciousness occurred."

Consroe et al[51]

reported cannabidiol (CBD) to produce dose-related improvements

in dystonic movement disorders. Malec et al[52] found spinal cord injured persons reported

decreased spasticity with marijuana use. Other papers

have also reported potential benefits of cannabinoids,

including crude marijuana[53][54],

and the synthetic Nabilone[55], where Martyn et al found clear improvement

in well-being, reduced pain from muscle spasm, and reduced

frequency of nocturia during the treatment condition

(1mg Nabilone every other day) compared to worsening

of symptoms during no treatment or placebo conditions.

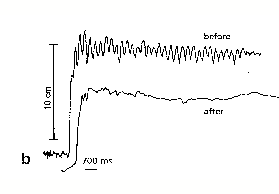

Meinck

et al[56] reported "The

chronic motor handicaps of a 30-year-old multiple sclerosis

patient acutely improved while he smoked a marihuana

cigarette. This effect was quantitatively assessed by

means of clinical rating, electromyographic investigation

of the leg flexor reflexes and electromagnetic recording

of the hand action tremor. It is concluded that cannabinoids

may have powerful beneficial effects on both spasticity

and ataxia that warrant further evaluation."

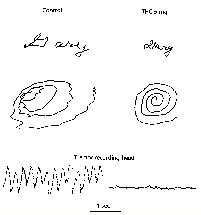

The improvements in tremor reported by Meinck &

Clifford are dramatically demonstrated in fig 4 below.

Fig

4 - Effects of THC on tremor in MS patients

Clifford

(1983)

Meinck et al (1989)

In

a small-scale Dutch trial on MS patients with severe

spasticity, Killestein et al[57] noted "Both

drugs were safe, but adverse events were more common

with plant-extract treatment. Compared with placebo,

neither THC nor plant-extract treatment reduced spasticity.

Both THC and plant-extract treatment worsened the participant's

global impression.", prompting Thompson

& Baker[58]

to conclude that the drug was potentially useful but

not yet ready for widespread clinical use. Smith[59], whilst accepting the cannabinoids effectivelyreduce

pain and spasticity in multiple sclerosis, highlighted

the limited evidence from available trials, and questioned

whether they are superior to conventional medications.

"Whether or not

cannabinoids do have therapeutic potential in the treatment

of MS, a further issue will be whether synthetic cannabinoids

should be used in preference to cannabis itself. Smoking

cannabis is associated with significant risks of lung

cancer and other respiratory dysfunction. Furthermore,

delta9-THC, as a broad-spectrum cannabinoid receptor

agonist, will activate both CB1 and CB2 receptors. Synthetic

cannabinoids, which target specific cannabinoid receptor

subtypes in specific parts of the CNS, are likely to

be of more therapeutic use than delta9-THC itself. If

rapid absorption is necessary, such synthetic drugs

could be delivered via aerosol formulations."

Fernandez[60] recognised the scientific basis and

called for more extensive and long-term clinical trials.

Clark[61] called

for reclassification of cannabis in the USA to allow

physicians to prescribe marijuana for MS. Williamson

& Evans[62] conducted

a wide ranging review into the therapeutic uses of cannabinoids,

commenting "Cannabis

is frequently used by patients with multiple sclerosis

(MS) for muscle spasm and pain, and in an experimental

model of MS low doses of cannabinoids alleviated tremor.

Most of the controlled studies have been carried out

with THC rather than cannabis herb and so do not mimic

the usual clinical situation." Mechoulam[63]

noted "Clinical

work in multiple sclerosis, which may lead to the approval

of tetrahydrocannabinol as a drug for this condition"

Schlicker et al[64] noted "Cannabis (marijuana)... has the potential for the

development of useful agents for the treatment of ...

multiple sclerosis." Carter & Rosen[65] reported "Marijuana

is a substance with many properties that may be applicable

to the management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

These include analgesia, muscle relaxation, bronchodilation,

saliva reduction, appetite stimulation, and sleep induction."

Guzman et al[66] concluded

"The neuroprotective

effect of cannabinoids may have potential clinical relevance

for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders such

as multiple sclerosis"

Cannabinoids

and Muscle Spasticity

In

1981 Petro & Ellenberger[67] noted "Spasticity is a common neurologic condition in patients

with multiple sclerosis, stroke, cerebral palsy or an

injured spinal cord. Animal studies suggest that THC

has an inhibitory effect on polysynaptic reflexes. Some

spastic patients claim improvement after inhaling cannabis"

and, in a mixed patient group, found "10

mg THC significantly reduced spasticity by clinical

measurement (P < 0.01)." In spinal

injury patients, Malec et al[68] found "spinal cord injured persons reported decreased spasticity

with marijuana use". The BMA report

recommended 'carefully controlled trials of cannabinoids in patients

with chronic spastic disorders which have not responded

to other drugs'

Pertwee[69] reported in 2002 "There is

a growing amount of evidence to suggest that cannabis

and individual cannabinoids may be effective in suppressing

certain symptoms of multiple sclerosis and spinal cord

injury, including spasticity and pain.",

noting "Clinical

... trials have shown that cannabis, Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol,

and nabilone can produce objective and/or subjective

relief from spasticity, pain, tremor, and nocturia in

patients with multiple sclerosis (8 trials) or spinal

cord injury (1 trial)." Pertwee &

Ross[70] noted "released

endocannabinoids mediate reductions both in inflammatory

pain and in the spasticity and tremor of multiple sclerosis".

Brooks et al[71]

reported "Activation

of cannabinoid receptors causes inhibition of spasticity"

Similarly,

Smith[72] noted "There

is a large amount of evidence to support the view that

the psychoactive ingredient in cannabis, delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol

(delta9-THC), and cannabinoids in general, can reduce

muscle spasticity and pain under some circumstances.

Cannabinoid (CB1) receptors in the CNS appear to mediate

both of these effects and endogenous cannabinoids may

fulfil these functions to some extent under normal circumstances"

while cautioning "it is still questionable whether cannabinoids are

superior to existing, conventional medications for the

treatment of spasticity and pain. In the case of spasticity,

there are too few controlled clinical trials to draw

any reliable conclusion at this stage."

In a 2001 review, Kalant[73] noted "Recent

evidence clearly demonstrates analgesic and anti-spasticity

effects that will probably prove to be clinically useful."

A

small Dutch clinical trial[74] found "Compared

with placebo, neither THC nor (cannabis) plant-extract

treatment reduced spasticity", prompting

Thomas & Baker[75] to question

whether western medicine was ready for cannabinoid therapy.

However, a larger scale trial of MS patients by GW Pharmaceuticals[76] reported

"THC:CBD medicine

provided a highly statistically significant improvement

in the symptom of spasticity".

There

is a large amount of research recently undertaken or

underway into the antispastic effects of cannabinoids,

particularly in patients with multiple sclerosis or

spinal injury. Less research effort has been conducted

to date into patients with spasticity arising from other

neurological conditions, although animal studies suggest

the anti-spastic effects of CB1 receptor agonists are

not confined to these conditions.

GW

Pharmaceuticals & Clinical Trials

In

November 2002, GW Pharmaceuticals reported the results

of Phase III clinical trials of cannabis-extract based

medicines on MS patients[77],

finding:

(a)

"In a double-blind parallel group study comparing

the efficacy of GW"s THC:CBD product with placebo

in the treatment of neuropathic pain in 66 patients

with MS, the THC:CBD medicine provided highly statistically

significant relief of pain in comparison with placebo

and highly statistically significant reduction in sleep

disturbance."

(b)

"In a double-blind parallel group study comparing

the efficacy of GW"s THC:CBD product with placebo

in the treatment of chronic refractory pain in 70 patients

with MS and other neurological conditions, the THC:CBD

medicine provided statistically significant pain relief

(as evidenced by the diminished use of analgesic rescue

medication) and statistically significant reduction

in sleep disturbance."

(c)

"In a double-blind parallel group study comparing

the efficacy of GW"s THC:CBD product with placebo

in the treatment of a number of symptoms in 160 patients

with MS, the THC:CBD medicine provided a highly statistically

significant improvement in the symptom of spasticity.

Positive trends were also observed in a number of other

MS symptoms (providing useful additional support to

significant results obtained in Phase II trials)."

Dr Philip Robson, GW Medical Director, commented: "These

rigorous randomised placebo-controlled trials indicate

that GW"s cannabis-based medicine can provide additional

benefits over and above that of standard treatments

in these serious and refractory neurological conditions.

The results show statistically significant reductions

in neuropathic pain, which is recognised as being difficult

to treat and is often particularly distressing. There

were also significant improvements in other symptoms

in patients with MS, notably spasticity and sleep disturbance.

In my opinion, it is this broad spectrum of activity,

coupled with an excellent safety profile, which gives

GW"s cannabis-based medicine the potential to make

a unique contribution towards improving the quality

of life of patients with these chronic disabling diseases."

Svendsen

et al[78] conducted a clinical trial in Denmark

using Dronabinol (synthetic THC) finding "Median

spontaneous pain intensity was significantly lower during

dronabinol treatment than during placebo treatment...

On the SF-36 quality of life scale, the two items bodily

pain and mental health indicated benefits from active

treatment compared with placebo", the

same team[79] later

reported "Dronabinol

reduced the spontaneous pain intensity significantly

compared with placebo" In a clinical

trial of cannabis extracts in Switzerland, Vaney et

al[80] noted

"trends in favour

of active treatment were seen for spasm frequency, mobility

and getting to sleep. In the 37 patients (per-protocol

set) who received at least 90% of their prescribed dose,

improvements in spasm frequency (P = 0.013) and mobility

after excluding a patient who fell and stopped walking

were seen (P = 0.01)" and concluded

"A standardized

Cannabis sativa plant extract might lower spasm frequency

and increase mobility with tolerable side effects in

MS patients with persistent spasticity not responding

to other drugs."

A

clinical trial of cannabis extracts on bladder function

in MS patients by Brady et al[81] found "Urinary

urgency, the number and volume of incontinence episodes,

frequency and nocturia all decreased significantly following

treatment (P <0.05, Wilcoxon's signed rank test).

However, daily total voided, catheterized and urinary

incontinence pad weights also decreased significantly

on both extracts. Patient self-assessment of pain, spasticity

and quality of sleep improved significantly (P <0.05,

Wilcoxon's signed rank test) with pain improvement continuing

up to median of 35 weeks. There were few troublesome

side effects" In a large-scale (n=630)

clinical trial of cannabis extract, THC and placebo

on bladder function Freeman et al[82] found "All

three groups showed a significant reduction, p<0.01,

in adjusted episode rate (i.e. correcting for baseline

imbalance) from baseline to the end of treatment: cannabis

extract, 38%; THC, 33%; and placebo, 18%. Both active

treatments showed significant effects over placebo (cannabis

extract, p=0.005; THC, p=0.039). Conclusion: The findings

are suggestive of a clinical effect of cannabis on incontinence

episodes in patients with MS."

A

clinical trial of Sativex on MS symptoms including spasticity,

spasms, bladder problems, tremor or pain by Wade et

al[83] reported "Following CBME the primary symptom score reduced from

mean (SE) 74.36 (11.1) to 48.89 (22.0) following CBME

and from 74.31 (12.5) to 54.79 (26.3) following placebo

[ns]. Spasticity VAS scores were significantly reduced

by CBME (Sativex) in comparison with placebo (P =0.001)."

A clinical trial of 1:1 THC/CBD Sativex on 66x MS patients

suffering central pain by Rog et al[84] found "(Sativex)

was superior to placebo in reducing the mean intensity

of pain (CBM mean change -2.7, 95% CI: -3.4 to -2.0,

placebo -1.4 95% CI: -2.0 to -0.8, comparison between

groups, p = 0.005) and sleep disturbance (CBM mean change

-2.5, 95% CI: -3.4 to -1.7, placebo -0.8, 95% CI: -1.5

to -0.1, comparison between groups, p = 0.003). CBM

was generally well tolerated, although more patients

on CBM than placebo reported dizziness, dry mouth, and

somnolence"

Reviewing

clinical trial evidence in 2005, Teare & Zajicek[85]

noted "Recent

clinical studies to treat symptoms of multiple sclerosis

have shown varying results, which may reflect issues

relating to the way in which such studies were conducted.

There is now increasing interest in the potential role

of cannabinoids not only in symptom relief, but also

for their possible neuroprotective actions."

Zajicek et al[86] followed up clinical trial patients

invited to continue treatment with THC, plant extract

or placebo for 12 months, finding a "small

treatment effect on muscle spasticity as measured by

change in Ashworth score from baseline to 12 months"

for THC (1.82) and extract (0.1) compared to placebo

(-0.23), and concluded "These data provide limited evidence for a longer term

treatment effect of cannabinoids. A long term placebo

controlled study is now needed to establish whether

cannabinoids may have a role beyond symptom amelioration

in MS." In a clinical review, Azad &

Rammes[87]

concluded "In

multiple sclerosis, cannabinoids have been shown to

have beneficial effects on spasticity, pain, tremor

and bladder dysfunction."

Solaro[88] conducted two clinical trials of Dronabinol

and Sativex on pain in MS patients, finding "Active

drugs were superior to placebo in reducing the mean

intensity of pain, although patients reported side effects

such as dizziness and somnolence more frequently"

In a clinical trial of sublingual extracts, Wade et

al[89] found "Pain

relief associated with both THC and CBD was significantly

superior to placebo. Impaired bladder control, muscle

spasms and spasticity were improved by CME in some patients

with these symptoms." In a clinical

trial studying effects of cannabinoids on tremor in

MS patients, Fox et al[90] found

"no significant

improvement in any of the objective measures of upper

limb tremor with cannabis extract compared to placebo.

Finger tapping was faster on placebo compared to cannabis

extract (p < 0.02). However, there was a nonsignificant

trend for patients to experience more subjective relief

from their tremors while on cannabis extract compared

to placebo" In a further clinical trial,

Notcutt et al[91]

studied the effect of extracts on relief of chronic

pain, finding "Extracts which contained THC proved most effective

in symptom control."

GW

Pharmaceuticals[92] reported interim results of clinical

trials in 2003, including "THC:CBD

(narrow ratio) caused statistically significant reductions

in neuropathic pain in patients with MS and other conditions.

In addition, improvements in other MS symptoms were

observed as well" and concluding "The phase II trials provided positive results and

confirmed an excellent safety profile for cannabis-based

medicines"

Reviewing

results of clinical trials, Corey[93] noted

"Two large trials

found that cannabinoids were significantly better than

placebo in managing spasticity in multiple sclerosis.

Patients self-reported greater sense of motor improvement

in multiple sclerosis than could be confirmed objectively.

In smaller qualifying trials, cannabinoids produced

significant objective improvement of tics in Tourette's

disease, and neuropathic pain. A new, non-psychotropic

cannabinoid also has analgesic activity in neuropathic

pain." Reviewing results of early clinical

trials in 2004, Smith[94] conceded "results

of preclinical trials also lend support to the hypothesis

that the endogenous cannabinoid system may be involved

in the regulation of spasticity and pain"

Fernandez-Ruiz et al[95] concluded

"the control

of movement is one of the more relevant physiological

roles of the endocannabinoid transmission in the brain"

Shakespeare

et al[96] criticised studies of spasticity which

failed to use the standardised åAshworth" scale

to score results. In a controlled clinical trial Zajicek

et al[97] found "Treatment with cannabinoids did not have a beneficial

effect on spasticity when assessed with the Ashworth

scale. However, though there was a degree of unmasking

among the patients in the active treatment groups, objective

improvement in mobility and patients' opinion of an

improvement in pain suggest cannabinoids might be clinically

useful." Killestein et al[98] conducted

a clinical trial of oral THC and cannabis plant extract

in 16 MS patients, finding both drugs to be safe but

neither to be effective at reducing spasticity, and

both åworsened the

participant"s global perception".

However, another paper from the same study[99] noted "The

results suggest pro-inflammatory disease-modifying potential

of cannabinoids in MS" Killestein et

al[100] concluded in 2004 that "convincing evidence that cannabinoids are effective

in MS is still lacking" and that "it

is also not possible to conclude definitely that cannabinoids

are ineffective"[101]

Russo

& Guy[102], of GW Pharmaceuticals, reported in

2006 "CBD is

demonstrated to antagonise some undesirable effects

of THC including intoxication, sedation and tachycardia,

while contributing analgesic, anti-emetic, and anti-carcinogenic

properties in its own right. In modern clinical trials,

this has permitted the administration of higher doses

of THC, providing evidence for clinical efficacy and

safety for cannabis based extracts in treatment of spasticity,

central pain and lower urinary tract symptoms in multiple

sclerosis, as well as sleep disturbances, (and) peripheral

neuropathic pain... The hypothesis that the combination

of THC and CBD increases clinical efficacy while reducing

adverse events is supported." Perez[103] reviewed the results of clinical trials

of Sativex, concluding "Clinical

assessment of this combined cannabinoid medicine has

demonstrated efficacy in patients with intractable pain

(chronic neuropathic pain, pain due to brachial plexus

nerve injury, allodynic peripheral neuropathic pain

and advanced cancer pain), rheumatoid arthritis and

multiple sclerosis (bladder problems, spasticity and

central pain), with no significant intoxication-like

symptoms, tolerance or withdrawal syndrome"

Treating

the disease process?

Increasing

evidence is emerging from receptor and animal studies

that cannabinoids may be involved in the degenerative

disease process involved in the development of MS, and

that cannabinoid therapy may offer hope of halting or

even reversing the disease process.

Molina-Holgado

et al[104] found anandamide (endogenous CB1 cannabinoid

receptor agonist) reduced the effects of encephalomyelitis

in mice, suggesting a receptor-mediated mode of action

in arresting or reducing the autoimmune response considered

to be involved in the MS disease process.

Van

Oosten et al[105] reported a case study of a 46 year

old woman treated for obesity with a cannabinoid-receptor

antagonist who developed MS some months later.

Jackson

et al[106] studied genetically-modified mice where

the CB1 receptors had been disabled, noting an increase

in demyelination responses, and concluding that the

results "strengthen

the hypothesis of neuroprotection elicited via cannabinoid

receptor 1 signaling." Pryce et al[107], in a study on neurodegeneration in

mice, concluded "in

addition to symptom management, cannabis may also slow

the neurodegenerative processes that ultimately lead

to chronic disability in multiple sclerosis"

In

rats, Carrier et al[108] noted "2-AG

activation of CB(2) receptors may contribute to the

proliferative response of microglial cells, as occurs

in neurodegenerative disorders" Kim

et al[109] reported "AM1241

is a cannabinoid CB2 receptor selective agonist that

has been shown to be effective in models of inflammation

and hyperalgesia... treatment with AM1241 was effective

at slowing signs of disease progression when administered

after onset of signs in an ALS mouse model (hSOD1(G93A)

transgenic mice). Administration at the onset of tremors

delayed motor impairment in treated mice when compared

to vehicle controls. Three conditions of ALS, the loss

of motor function, paralysis scoring and weight loss,

were analyzed using a mathematical model. Loss of motor

function (as assessed by performance on a rotarod) was

delayed by 12.5 days in male mice by AM1241. In female

mice, AM1241 extended rotarod performance by 3 days,

although this was not statistically significant. In

male mice, AM1241 also extended by 5 days the time to

reach the 50% point on a visually-assessed performance

scale."

Stella[110] investigated the effect of cannabinoids

on glial cells involved in the MS disease process, noting

"Recent evidence suggests that glial cells also express

components of the cannabinoid signaling system and marijuana-derived

compounds act at CB receptors expressed by glial cells,

affecting their functions" Following

a tissue-culture study showing that JWH-015 - a CB2

agonist, reduced neurodegenerative activity in microglial

cells, Ehrhart et al[111] postulated "beneficial

effects provided by cannabinoid receptor CB2 modulation

in neurodegenerative diseases" Eljaschewitsch

et al[112]

found "the endocannabinoid

anandamide (AEA) protects neurons from inflammatory

damage by CB(1/2) receptor-mediated rapid induction

of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 (MKP-1)

in microglial cells" Tagliaferro et

al[113] reported "long-term neuroprotective

effects observed after cannabinoid treatments"

Fujiwara

et al[114] reported "Delta9-THC

markedly inhibited the neurodegeneration in experimental

allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE), an animal model of

multiple sclerosis and reduced the elevated glutamate

level of cerebrospinal fluid induced by EAE. These therapeutic

effects on EAE were reversed by SR141716A"

Yang et al[115] reported "ameliorating

effects of cannabinoids on axonal injury associated

with multiple sclerosis are achieved by its direct action"

Reviewing neurodegenerative studies, Yiangou et al[116] concluded

"CB2 specific

agonists deserve evaluation in the progression of MS

and ALS" Witting et al[117]

reported "activation

of cannabinoid receptors reduces the production and

diffusion of harmful mediators" Bilsland

et al[118] concluded "cannabinoids

have significant neuroprotective effects"

Jackson

et al[119] concluded "neuroprotection

could be elicited through the cannabinoid receptor 1,

and point towards a potential therapeutic role for cannabinoid

compounds in demyelinating conditions such as multiple

sclerosis", further concluding[120] "There

is increasing evidence for cannabinoid-mediated control

of symptoms, which is being more supported by the underlying

biology. However there is accumulating evidence in vitro

and in vivo to support the hypothesis that the cannabinoid

system can limit the neurodegenerative possesses that

drive progressive disease, and may provide a new avenue

for disease control."

Learned

Reviews

Taylor[121], reviewing potential medical uses in

1998, concluded: "Marijuana

shows clinical promise for... spasticity, multiple sclerosis...

As a medical drug, marijuana should be available for

patients who do not adequately respond to currently

available therapies."

In

2002 reviews, Grundy[122] reports "Cannabinoids

... provide symptomatic relief in experimental models

of chronic neurodegenerative diseases, such as multiple

sclerosis and Huntington's disease",

but cautioned "Our

understanding of cannabinoid neurobiology, however,

must improve if we are to effectively exploit this system

and take advantage of the numerous characteristics that

make this group of compounds potential neuroprotective

agents." Pertwee[123] notes "Clinical

evidence comes from trials, albeit with rather small

numbers of patients. These trials have shown that cannabis,

Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol, and nabilone can produce

objective and/or subjective relief from spasticity,

pain, tremor, and nocturia in patients with multiple

sclerosis (8 trials)", noting "...experiments,

... with mice ... have provided strong evidence that

cannabinoid-induced reductions in tremor and spasticity

are mediated by cannabinoid receptors."

Pertwee & Ross[124] concluded "Potential

therapeutic uses of cannabinoid receptor agonists include

the management of multiple sclerosis/spinal cord injury,

pain, inflammatory disorders, glaucoma, bronchial asthma,

vasodilation that accompanies advanced cirrhosis, and

cancer."

In

a 2002 review Smith[125] concluded "There

is a large amount of evidence to support the view that

the psychoactive ingredient in cannabis, delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol

(delta9-THC), and cannabinoids in general, can reduce

muscle spasticity and pain under some circumstances.

Cannabinoid (CB1) receptors in the CNS appear to mediate

both of these effects and endogenous cannabinoids may

fulfil these functions to some extent under normal circumstances.

However, in the context of multiple sclerosis (MS),

it is still questionable whether cannabinoids are superior

to existing, conventional medications for the treatment

of spasticity and pain. ... Synthetic cannabinoids,

which target specific cannabinoid receptor subtypes

in specific parts of the CNS, are likely to be of more

therapeutic use than delta9-THC itself"

Contemporaneously, Pertwee[126] concluded

"There is a growing

amount of evidence to suggest that cannabis and individual

cannabinoids may be effective in suppressing certain

symptoms of multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury,

including spasticity and pain.", noting

that "trials have shown that cannabis, Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol,

and nabilone can produce objective and/or subjective

relief from spasticity, pain, tremor, and nocturia in

patients with multiple sclerosis (8 trials) or spinal

cord injury (1 trial). The clinical evidence is supported

by results from experiments with animal models of multiple

sclerosis. Some of these experiments, performed with

mice with chronic relapsing experimental allergic encephalomyelitis

(CREAE), have provided strong evidence that cannabinoid-induced

reductions in tremor and spasticity are mediated by

cannabinoid receptors, both CB(1) and CB(2)."

In 2005 Smith[127] qualified his skepticism, noting "The evidence for the therapeutic efficacy of cannabinoids

in the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS) is increasing

but is not as yet convincing. Although several trials

have reported no significant effect, the majority of

the evidence which supports a beneficial effect on spasticity

and pain is based on subjective measurements in trials

where unblinding was likely to be a problem. The available

clinical trial data suggest that the adverse side effects

associated with using cannabis-based medicinal extracts

(CBMEs) are generally mild, such as dry mouth, dizziness,

somnolence, nausea and intoxication, and in no case

did toxicity develop."

Baker

& Pryce[128] noted "those

with multiple sclerosis, claim that it may offer benefit

in symptom control. Cannabis exerts many of its effects

because it taps into an endogenous cannabinoid system...

Cannabinoids provide a novel therapeutic target, not

only for controlling symptoms, but also slowing disease

progression through inhibition of neurodegeneration,

which is the cause of accumulating irreversible disability."

Pryce & Baker[129] concluded

"abundant experimental

data have reinforced the anecdotal claims of people

who perceive medicinal benefit from the currently illegal

consumption of cannabis. This, combined with data from

recent clinical trials, points to the prospect of cannabis

as a medication in the treatment of multiple sclerosis

and numerous other medical conditions."

Croxford

& Miller[130], reviewing early clinical trials, noted

"recent research

in animal models of multiple sclerosis has demonstrated

the efficacy of cannabinoids in controlling disease-induced

symptoms such as spasticity and tremor, as well as in

ameliorating the severity of clinical disease. However,

these initially promising results have not yet been

fully translated into the clinic. Although cannabinoid

treatment of multiple sclerosis symptoms has been shown

to be both well tolerated and effective in a number

of subjective tests in several small-scale clinical

trials, objective measures demonstrating the efficacy

of cannabinoids are still lacking."

Reviewing clinical trial and animal evidence, Schwarz

et al[131] concluded "Many

patients use cannabis to alleviate spasticity and pain.

Small series indicated positive effects, but randomized

trials were negative for spasticity. However, many patients

report subjective improvement under cannabis even if

their objective parameters remain unchanged"

Trebst & Sangel concluded "there

is reasonable evidence for the therapeutical employment

of cannabinoids in the treatment of MS related symptoms.

Furthermore, data are arising that cannabinoids have

immunomodulatory and neuroprotective properties. However,

results from clinical trials do not allow the recommendation

for the general use of cannabinoids in MS"

In

December 2005, Malfitano et al[132] summarised the state

of knowledge of the pharmacological, neuroanatomical

and biochemical mechanisms behind the role of cannabinoids

in MS thus "An

increasing body of evidence suggests that cannabinoids

have beneficial effects on the symptoms of multiple

sclerosis, including spasticity and pain. Endogenous

molecules with cannabinoid-like activity, such as the

"endocannabinoids", have been shown to mimic

the anti-inflammatory properties of cannabinoids through

the cannabinoid receptors. Several studies suggest that

cannabinoids and endocannabinoids may have a key role

in the pathogenesis and therapy of multiple sclerosis.

Indeed, they can down regulate the production of pathogenic

T helper 1-associated cytokines enhancing the production

of T helper 2-associated protective cytokines. A shift

towards T helper 2 has been associated with therapeutic

benefit in multiple sclerosis. In addition, cannabinoids

exert a neuromodulatory effect on neurotransmitters

and hormones involved in the neurodegenerative phase

of the disease. In vivo studies using mice with experimental

allergic encephalomyelitis, an animal model of multiple

sclerosis, suggest that the increase of the circulating

levels of endocannabinoids might have a therapeutic

effect, and that agonists of endocannabinoids with low

psychoactive effects could open new strategies for the

treatment of multiple sclerosis."

Pertwee[133] summarised "CB1

and/or CB2 receptor activation appears to ameliorate

inflammatory and neuropathic pain and certain multiple

sclerosis symptoms. This might be exploited clinically

by using CB1, CB2 or CB1/CB2 agonists, or inhibitors

of the membrane transport or catabolism of endocannabinoids

that are released in increased amounts, at least in

animal models of pain and multiple sclerosis."

McFarland et al[134][135] concluded

"augmentation

of cannabinergic tone might be therapeutically beneficial

in the treatment of multiple disease states such as

chronic pain, anxiety, multiple sclerosis, and neuropsychiatric

disorders"

Summary

- Cannabinoids and M.S.

Multiple

Sclerosis is a disease for which conventional medication

provides little benefit.

There

is a wealth of anecdotal evidence from MS patients reporting

dramatic improvement in symptoms following illicit use

of cannabis, from case histories and from surveys.

The

results of early small-scale clinical trials were mixed,

although more recent large scale clinical trials have

shown THC and cannabis extracts can improve, in some

cases dramatically, symptoms of MS such as pain, ataxia,

muscle spasm, spasticity, bladder dysfunction and tremor

in many (but not all) patients. Studies failing to find,

or finding non-significant effects, have tended to use

subtherapeutic doses.

Recent

animal research has indicated a direct receptor mediated

immunosuppressive effect on microglial cells in the

brain tissues which may delay or in some cases reverse

the neurodegenerative process in MS-like animal models.

This provides growing evidence that cannabinoids may

not only benefit the symptoms of MS, but may potentially

provide a treatment for the disease process itself,

offering unprecedented hope to sufferers of the disease.

The

House of Lords Science & Technology Committee recommended

in 1998 that clinical trials of cannabinoids in the

treatment of MS be undertaken as a matter of urgency,

and that pending the award of product licences, doctors

should be allowed to prescribe cannabis or cannabis

resin as an unlicensed medicine on a named-patient basis

for patients, including MS sufferers. In 2001, they

went further and recommended that cannabis preparations

be legalised for medical use. Since 1998 scientific

investigation of the effects and causes of cannabinoid

action on MS and symptoms has exploded, with the vast

majority of studies and reviewers showing a potential

therapeutic benefit. However the Medicines Control Agency

(MCA) and National Institute for Clinical Excellence

(NICE) have yet to licence cannabis, THC or Sativex

for routine medical prescription.

Clinical

trials of the extract Sativex containing roughly equal quantities

of THC and CBD have found the combination more effective

than THC alone, largely due to the increased amount

of THC which can be administered before patients develop

a åhigh", but also due to the anti-inflammatory

effects of CBD.

M.J.Atha

© IDMU Ltd - September 2006

References

[1]

Macpherson G. (ed) [1995] Black"s Medical Dictionary

38th Edition. London: A&C Black pp332-333

[2]

House of Lords [1998] op cit para 5.19

[3]

Grinspoon L & Bakalar JB (1997) Marijuana - Forbidden

Medicine (2nd Ed). Yale University Press

[5]

Consroe P, Musty R, Rein J, Tillery W, Pertwee R (1997)

The perceived effects of smoked cannabis on patients

with multiple sclerosis. Eur Neurol 38(1):44-8

[6]

Schnelle M, Grotenhermen F, Reif M, Gorter RW (1999)

[Results of a standardized survey on the medical use

of cannabis products in the German-speaking area]. [Article

in German] Forsch Komplementarmed 6 Suppl 3:28-36

[7]

Mechoulam R (1999) Recent advantages in cannabinoid

research. Forsch Komplementarmed 6 Suppl 3:16-20

[8]

Somerset M, Campbell R, Sharp DJ, Peters TJ [2000] What

do people with MS want and expect from health-care services?

Health Expect 4(1):29-37

[9]

Page SA, Verhoef MJ, Stebbins RA, Metz LM, Levy JC.

[2003] Cannabis use as described by people with multiple

sclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci. 30(3):201-5.

[10]

Amtmann D, Weydt P, Johnson KL, Jensen MP, Carter GT.

[2004] Survey of cannabis use in patients with amyotrophic

lateral sclerosis. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 21(2):95-104.

[11]

Simmons RD, Ponsonby AL, van der Mei IA, Sheridan P.

[2004] What affects your MS? Responses to an anonymous,

Internet-based epidemiological survey. Mult Scler. 2004

Apr;10(2):202-11.

[12]

Clark AJ, Ware MA, Yazer E, Murray TJ, Lynch ME. [2004]

Patterns of cannabis use among patients with multiple

sclerosis. Neurology. 62(11):2098-100.

[13]

Ware MA, Adams H, Guy GW. [2005] The medicinal use of

cannabis in the UK: results of a nationwide survey.

Int J Clin Pract. 59(3):291-5.

[14]

Erkens JA, Janse AF, Herings RM. [2005] Limited use

of medicinal cannabis but for labeled indications after

legalization. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 14(11):821-2

[15]

LymanWD, Sonett JR, Brosnan CF, Elkin R & Bornstein

MB (1989) Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol: an novel treatment

for Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Journal

of Neuroimmunology 23 pp73-81

[16]

Wirguin I, Mechoulam R, Breuer A, Schezen E, Weidenfeld

J & Brenner T (1994) Suppression of Experimental

Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis by cannabinoids. Immunopharmacology

28(3) pp209-214

[17]

Baker D, Pryce G, Croxford JL, Brown P, Pertwee RG,

Huffman JW, Layward L (2000) Cannabinoids control spasticity

and tremor in a multiple sclerosis model. Nature 404(6773):84-7

[18]

Achiron A, Miron S, Lavie V, Margalit R, Biegon A (2000)

Dexanabinol (HU-211) effect on experimental autoimmune

encephalomyelitis: implications for the treatment of

acute relapses of multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol

102(1):26-31

[19]

Pop E. [2000] Dexanabinol Pharmos. Curr Opin Investig

Drugs 1(4):494-503

[20]

Berrendero F, Sanchez A, Cabranes A, Puerta C, Ramos

JA, Garcia-Merino A, Fernandez-Ruiz J. [2001] Changes

in cannabinoid CB(1) receptors in striatal and cortical

regions of rats with experimental allergic encephalomyelitis,

an animal model of multiple sclerosis. Synapse 41(3):195-202

[21]

Baker D, Pryce G, Croxford JL, Brown P, Pertwee RG,

Makriyannis A, Khanolkar A, Layward L, Fezza F, Bisogno

T, Di Marzo V [2001] Endocannabinoids control spasticity

in a multiple sclerosis model. FASEB J 15(2):300-2

[22]

Di Marzo V, Bifulco M, De Petrocellis L (2000) Endocannabinoids

and multiple sclerosis: a blessing from the 'inner bliss'?

Trends Pharmacol Sci 21(6):195-7

[23]

Pop E (2000) Dexanabinol Pharmos. Curr Opin Investig

Drugs 1(4):494-503

[24]

Baker D, Pryce G, Croxford JL, Brown P, Pertwee RG,

Makriyannis A, Khanolkar A, Layward L, Fezza F, Bisogno

T, Di Marzo V (2001) Endocannabinoids control spasticity

in a multiple sclerosis model. FASEB J 15(2):300-2

[25]

Pertwee RG (1999) Cannabis and cannabinoids: pharmacology

and rationale for clinical use. Forsch Komplementarmed

6 Suppl 3:12-5

[26]

Pertwee RG (1999) Pharmacology of cannabinoid receptor

ligands. Curr Med Chem 6(8):635-64

[27]

Killestein J, Nelemans SA (1997) [Therapeutic applications

and biomedical effects of cannabinoids; pharmacological

starting points]. [Article in Dutch] Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd

141(35):1689-93

[28]

Klein TW, Newton CA, Friedman H [2001] Cannabinoids

and the immune system. Pain Res Manag 6(2):95-101

[29]

Lambert DM, Vandevoorde S, Jonsson KO, Fowler CJ. [2002]

The palmitoylethanolamide family: a new class of anti-inflammatory

agents? Curr Med Chem 9(6):663-74

[30]

Wilkinson JD, Whalley BJ, Baker D, Pryce G, Constanti

A, Gibbons S, Williamson EM. [2003] Medicinal cannabis:

is delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol necessary for all its

effects? J Pharm Pharmacol. 55(12):1687-94.

[31]

Ni X, Geller EB, Eppihimer MJ, Eisenstein TK, Adler

MW, Tuma RF. [2004] Win 55212-2, a cannabinoid receptor

agonist, attenuates leukocyte/endothelial interactions

in an experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis model.

Mult Scler. 10(2):158-64

[32]

Raman C, McAllister SD, Rizvi G, Patel SG, Moore DH,

Abood ME. [2004] Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: delayed

disease progression in mice by treatment with a cannabinoid.

Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 5(1):33-9.

[33]

Mestre L, Correa F, Arevalo-Martin A, Molina-Holgado

E, Valenti M, Ortar G, Di Marzo V, Guaza C. [2005] Pharmacological

modulation of the endocannabinoid system in a viral

model of multiple sclerosis. J Neurochem. 92(6):1327-39.

[34]

Weydt P, Hong S, Witting A, Moller T, Stella N, Kliot

M. [2005] Cannabinol delays symptom onset in SOD1 (G93A)

transgenic mice without affecting survival. Amyotroph

Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 6(3):182-4.

[35]

Ortega-Gutierrez S, Molina-Holgado E, Arevalo-Martin

A, Correa F, Viso A, Lopez-Rodriguez ML, Di Marzo V,

Guaza C. [2005] Activation of the endocannabinoid system

as therapeutic approach in a murine model of multiple

sclerosis. FASEB J 19(10):1338-40

[36]

de Lago E, Fernandez-Ruiz J, Ortega-Gutierrez S, Cabranes

A, Pryce G, Baker D, Lopez-Rodriguez M, Ramos JA. [2006]

UCM707, an inhibitor of the anandamide uptake, behaves

as a symptom control agent in models of Huntington's

disease and multiple sclerosis, but fails to delay/arrest

the progression of different motor-related disorders.

Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 16(1):7-18.

[37]

Arevalo-Martin A, Vela JM, Molina-Holgado E, Borrell

J, Guaza C. [2003] Therapeutic action of cannabinoids

in a murine model of multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci.

23(7):2511-6.

[38]

Croxford JL, Miller SD. [2003] Immunoregulation of a

viral model of multiple sclerosis using the synthetic

cannabinoid R+WIN55,212. J Clin Invest. 111(8):1231-40.

[39]

Cabranes A, Pryce G, Baker D, Fernandez-Ruiz J. [2006]

Changes in CB(1) receptors in motor-related brain structures

of chronic relapsing experimental allergic encephalomyelitis

mice. Brain Res. 1107(1):199-205

[40]

Clark PA (2000) The ethics of medical marijuana: government

restrictions vs. medical necessity. J Public Health

Policy 21(1):40-60

[41]

Rosenthal MS, Kleber HD (1999) Making sense of medical

marijuana. Proc Assoc Am Physicians 111(2):159-65

[42]

Masood E (1998) Cannabis laws 'threaten validity of

trials'. Nature 396(6708):206

[43]

Robson P. [2005] Human studies of cannabinoids and medicinal

cannabis. Handb Exp Pharmacol. (168):719-56.

[44]

Petro DJ, Ellenberger C Jr (1981) Treatment of human

spasticity with delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol. J Clin

Pharmacol 21(8-9 Suppl):413S-416S

[45]

Ungerleider JT, Andyrsiak T, Fairbanks L, Ellison GW,

Myers LW (1987) Delta-9-THC in the treatment of spasticity

associated with multiple sclerosis. Adv Alcohol Subst

Abuse 7(1):39-50

[46]

Clifford DB (1983) Tetrahydrocannabinol for tremor in

multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 13(6):669-71

[47]

Schon F, Hart PE, Hodgson TL, Pambakian AL, Ruprah M,

Williamson EM, Kennard C (1999) Suppression of pendular

nystagmus by smoking cannabis in a patient with multiple

sclerosis. Neurology 53(9):2209-10

[48]

Dell'Osso LF (2000) Suppression of pendular nystagmus

by smoking cannabis in a patient with multiple sclerosis.

Neurology 54(11):2190-3

[49]

Brenneisen R, Egli A, Elsohly MA, Henn V, Spiess Y (1996)

The effect of orally and rectally administered delta

9-tetrahydrocannabinol on spasticity: a pilot study

with 2 patients. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 34(10):446-52

[50]

Maurer M, Henn V, Dittrich A, Hofmann A (1990) Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol

shows antispastic and analgesic effects in a single

case double-blind trial. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol

Sci 1990;240(1):1-4

[51]

Consroe P, Sandyk R, Snider SR (1986) Open label evaluation

of cannabidiol in dystonic movement disorders. Int J

Neurosci 30(4):277-82

[52]

Malec J, Harvey RF, Cayner JJ (1982) Cannabis effect

on spasticity in spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil

63(3):116-8

[53]

Petro DJ (1980) Marihuana as a therapeutic agent for

muscle spasm or spasticity. Psychosomatics 21(1):81,

85

[54]

Check WA (1979) Marijuana may lessen spasticity of MS.

JAMA 241(23):2476

[55]

Martyn CN, Illis LS, Thom J (1995) Nabilone in the treatment

of multiple sclerosis. Lancet 345(8949):579

[56]

Meinck HM, Schonle PW, Conrad B (1989) Effect of cannabinoids

on spasticity and ataxia in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol

236(2):120-2

[57]

Killestein J, Hoogervorst EL, Reif M, Kalkers NF, Van

Loenen AC, Staats PG, Gorter RW, Uitdehaag BM, Polman

CH. [2002] Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of orally

administered cannabinoids in MS. Neurology 58(9):1404-7

[58]

Thompson AJ, Baker D. [2002] Cannabinoids in MS: potentially

useful but not just yet! Neurology58(9):1323-4

[59]

Smith PF. [2002] Cannabinoids in the treatment of pain

and spasticity in multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Investig

Drugs 3(6):859-64

[60]

Lorenzo Fernandez P (2000) [No title available].[Article

in Spanish] An R Acad Nac Med (Madr) 117(3):595-605;

discussion 616-24

[61]

Clark PA (2000) The ethics of medical marijuana: government

restrictions vs. medical necessity. J Public Health

Policy 2000;21(1):40-60

[62]

Williamson EM, Evans FJ (2000) Cannabinoids in clinical

practice. Drugs 60(6):1303-14

[63]

Mechoulam R, Hanu L. [2001] The cannabinoids: An overview.

Therapeutic implications in vomiting and nausea after

cancer chemotherapy, in appetite promotion, in multiple

sclerosis and in neuroprotection. Pain Res Manag 6(2):67-73

[64]

Schlicker E, Kathmann M. [2001] Modulation of transmitter

release via presynaptic cannabinoid receptors. Trends

Pharmacol Sci 22(11):565-72

[65]

Carter GT, Rosen BS [2001] Marijuana in the management

of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Hosp Palliat

Care 18(4):264-70

[66]

Guzman M, Sanchez C, Galve-Roperh I. [2001] Control

of the cell survival/death decision by cannabinoids.

J Mol Med 78(11):613-25

[67]

Petro DJ, Ellenberger C Jr [1981] Treatment of human

spasticity with delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol. J Clin

Pharmacol 21(8-9 Suppl):413S-416S

[68]

Malec J, Harvey RF, Cayner JJ. [1982] Cannabis effect

on spasticity in spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil

63(3):116-8

[69]

Pertwee R. [2002] Cannabinoids and multiple sclerosis.

Pharmacol Ther 2002 Aug;95(2):165

[70]

Pertwee RG, Ross RA. [2002] Cannabinoid receptors and

their ligands. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids

66(2-3):101-21

[71]

Brooks JW, Pryce G, Bisogno T, Jaggar SI, Hankey DJ,

Brown P, Bridges D, Ledent C, Bifulco M, Rice AS, Di

Marzo V, Baker D. [2002] Arvanil-induced inhibition

of spasticity and persistent pain: evidence for therapeutic

sites of action different from the vanilloid VR1 receptor

and cannabinoid CB(1)/CB(2) receptors. Eur J Pharmacol

439(1-3):83-92

[72]

Smith PF. [2002] Cannabinoids in the treatment of pain

and spasticity in multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Investig

Drugs 3(6):859-64

[73]

Kalant H. [2001] Medicinal use of cannabis: history

and current status. Pain Res Manag 6(2):80-91

[74]

Killestein J, Hoogervorst EL, Reif M, Kalkers NF, Van

Loenen AC, Staats PG, Gorter RW, Uitdehaag BM, Polman

CH. [2002] Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of orally

administered cannabinoids in MS. Neurology 58(9):1404-7

[75]

Thompson AJ, Baker D. [2002] Cannabinoids in MS: potentially

useful but not just yet! Neurology 58(9):1323-4

[78]

Svendsen KB, Jensen TS, Bach FW. [2004] Does the cannabinoid

dronabinol reduce central pain in multiple sclerosis?

Randomised double blind placebo controlled crossover

trial. BMJ. 329(7460):253

[79]

Svendsen KB, Jensen TS, Bach FW. [2005] [Effect of the

synthetic cannabinoid dronabinol on central pain in

patients with multiple sclerosis--secondary publication]

[Article in Danish] Ugeskr Laeger. 167(25-31):2772-4.

[80]

Vaney C, Heinzel-Gutenbrunner M, Jobin P, Tschopp F,

Gattlen B, Hagen U, Schnelle M, Reif M. [2004] Efficacy,

safety and tolerability of an orally administered cannabis

extract in the treatment of spasticity in patients with

multiple sclerosis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled,

crossover study. Mult Scler. 10(4):417-24.

[81]

Brady CM, DasGupta R, Dalton C, Wiseman OJ, Berkley

KJ, Fowler CJ. [2004] An open-label pilot study of cannabis-based

extracts for bladder dysfunction in advanced multiple

sclerosis. Mult Scler. 10(4):425-33.

[82]

Freeman RM, Adekanmi O, Waterfield MR, Waterfield AE,

Wright D, Zajicek J. [2006] The effect of cannabis on

urge incontinence in patients with multiple sclerosis:

a multicentre, randomised placebo-controlled trial (CAMS-LUTS).

Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006 Mar 22;

[Epub ahead of print]

[83]

Wade DT, Makela P, Robson P, House H, Bateman C. [2004]

Do cannabis-based medicinal extracts have general or

specific effects on symptoms in multiple sclerosis?

A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study

on 160 patients. Mult Scler. 10(4):434-41.

[84]

Rog DJ, Nurmikko TJ, Friede T, Young CA. [2005] Randomized,

controlled trial of cannabis-based medicine in central

pain in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 65(6):812-9.

[85]

Teare L, Zajicek J. [2005] The use of cannabinoids in

multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 14(7):859-69.

[86]

Zajicek JP, Sanders HP, Wright DE, Vickery PJ, Ingram

WM, Reilly SM, Nunn AJ, Teare LJ, Fox PJ, Thompson AJ.

[2005] Cannabinoids in multiple sclerosis (CAMS) study:

safety and efficacy data for 12 months follow up. J

Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 76(12):1664-9.

[87]

Azad SC, Rammes G. [2005] Cannabinoids in anaesthesia

and pain therapy. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 18(4):424-7.

[88]

Solaro C. [2006] Epidemiology and treatment of pain

in multiple sclerosis subjects. Neurol Sci. 27 Suppl

4:s291-3.

[89]

Wade DT, Robson P, House H, Makela P, Aram J.[2003]

A preliminary controlled study to determine whether

whole-plant cannabis extracts can improve intractable

neurogenic symptoms. Clin Rehabil. 17(1):21-9.

[90]

Fox P, Bain PG, Glickman S, Carroll C, Zajicek J. [2004]

The effect of cannabis on tremor in patients with multiple

sclerosis. Neurology. 62(7):1105-9.

[91]

Notcutt W, Price M, Miller R, Newport S, Phillips C,

Simmons S, Sansom C. [2004] Initial experiences with

medicinal extracts of cannabis for chronic pain: results

from 34 'N of 1' studies. Anaesthesia. 59(5):440-52

[92]

[No authors listed] [2003] Cannabis-based medicines--GW

pharmaceuticals: high CBD, high THC, medicinal cannabis--GW

pharmaceuticals, THC:CBD. Drugs R D. 4(5):306-9.

[93]

Corey S. [2005] Recent developments in the therapeutic

potential of cannabinoids. P R Health Sci J. 24(1):19-26.

[94]

Smith PF. [2004] Medicinal cannabis extracts for the

treatment of multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Investig

Drugs. 5(7):727-30.

[95]

Fernandez-Ruiz J, Lastres-Becker I, Cabranes A, Gonzalez

S, Ramos JA. [2002] Endocannabinoids and basal ganglia

functionality. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids.

66(2-3):257-67.

[96]

Shakespeare DT, Boggild M, Young C. [2003] Anti-spasticity

agents for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev. (4):CD001332

[97]

Zajicek J, Fox P, Sanders H, Wright D, Vickery J, Nunn

A, Thompson A; UK MS Research Group. [2003] Cannabinoids

for treatment of spasticity and other symptoms related

to multiple sclerosis (CAMS study): multicentre randomised

placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 362(9395):1517-26.

[98]

Killestein J, Hoogervorst EL, Reif M, Kalkers NF, Van

Loenen AC, Staats PG, Gorter RW, Uitdehaag BM, Polman

CH. [2002] Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of orally

administered cannabinoids in MS. Neurology. 58(9):1404-7.

[99]

Killestein J, Hoogervorst EL, Reif M, Blauw B, Smits

M, Uitdehaag BM, Nagelkerken L, Polman CH. [2003] Immunomodulatory

effects of orally administered cannabinoids in multiple

sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 137(1-2):140-3.

[100]

Killestein J, Uitdehaag BM, Polman CH. [2004] Cannabinoids

in multiple sclerosis: do they have a therapeutic role?

Drugs. 64(1):1-11.

[101]

Killestein J, Bet PM, van Loenen AC, Polman CH. [2004]

[Medicinal cannabis for diseases of the nervous system:

no convincing evidence of effectiveness] [Article in

Dutch] Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 148(48):2374-8.

[102]

Russo E, Guy GW. [2006] A tale of two cannabinoids:

the therapeutic rationale for combining tetrahydrocannabinol

and cannabidiol. Med Hypotheses. 66(2):234-46.

[103]

Perez J. [2006] Combined cannabinoid therapy via an

oromucosal spray. Drugs Today (Barc). 42(8):495-503.

[104]

Molina-Holgado F, Molina-Holgado E, Guaza C (1998) The

endogenous cannabinoid anandamide potentiates interleukin-6

production by astrocytes infected with Theiler's murine

encephalomyelitis virus by a receptor-mediated pathway.

FEBS Lett 14;433(1-2):139-42

[105]

van Oosten BW, Killestein J, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Polman

CH. [2004] Multiple sclerosis following treatment with

a cannabinoid receptor-1 antagonist. Mult Scler. 10(3):330-1.

[106]

Jackson SJ, Pryce G, Diemel LT, Cuzner ML, Baker D.

[2005] Cannabinoid-receptor 1 null mice are susceptible

to neurofilament damage and caspase 3 activation. Neuroscience.

134(1):261-8.

[107]

Pryce G, Ahmed Z, Hankey DJ, Jackson SJ, Croxford JL,

Pocock JM, Ledent C, Petzold A, Thompson AJ, Giovannoni

G, Cuzner ML, Baker D. [2003] Cannabinoids inhibit neurodegeneration

in models of multiple sclerosis. Brain. 126(Pt 10):2191-202.

[108]

Carrier EJ, Kearn CS, Barkmeier AJ, Breese NM, Yang

W, Nithipatikom K, Pfister SL, Campbell WB, Hillard

CJ. [2004] Cultured rat microglial cells synthesize

the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonylglycerol, which increases

proliferation via a CB2 receptor-dependent mechanism.

Mol Pharmacol. 65(4):999-1007.

[109]

Kim K, Moore DH, Makriyannis A, Abood ME. [2006] AM1241,

a cannabinoid CB2 receptor selective compound, delays

disease progression in a mouse model of amyotrophic

lateral sclerosis. Eur J Pharmacol. 542(1-3):100-5.

[110]

Stella N. [2004] Cannabinoid signaling in glial cells.

Glia. 48(4):267-77.

[111]

Ehrhart J, Obregon D, Mori T, Hou H, Sun N, Bai Y, Klein

T, Fernandez F, Tan J, Shytle RD. [2005] Stimulation

of cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2) suppresses microglial

activation. J Neuroinflammation. 12;2:29.

[112]